In conversation with: Caroline Japal.

AKIN (2023)

Caroline Japal

H: 210mm x W: 160mm x D: 70mm

Dark blue hardcover book, with handmade paper, binded with yellow threads, and a spine decorated with wooden hair beads, amethyst & jade crystals, pearls, cowrie shells, and golden accessories.

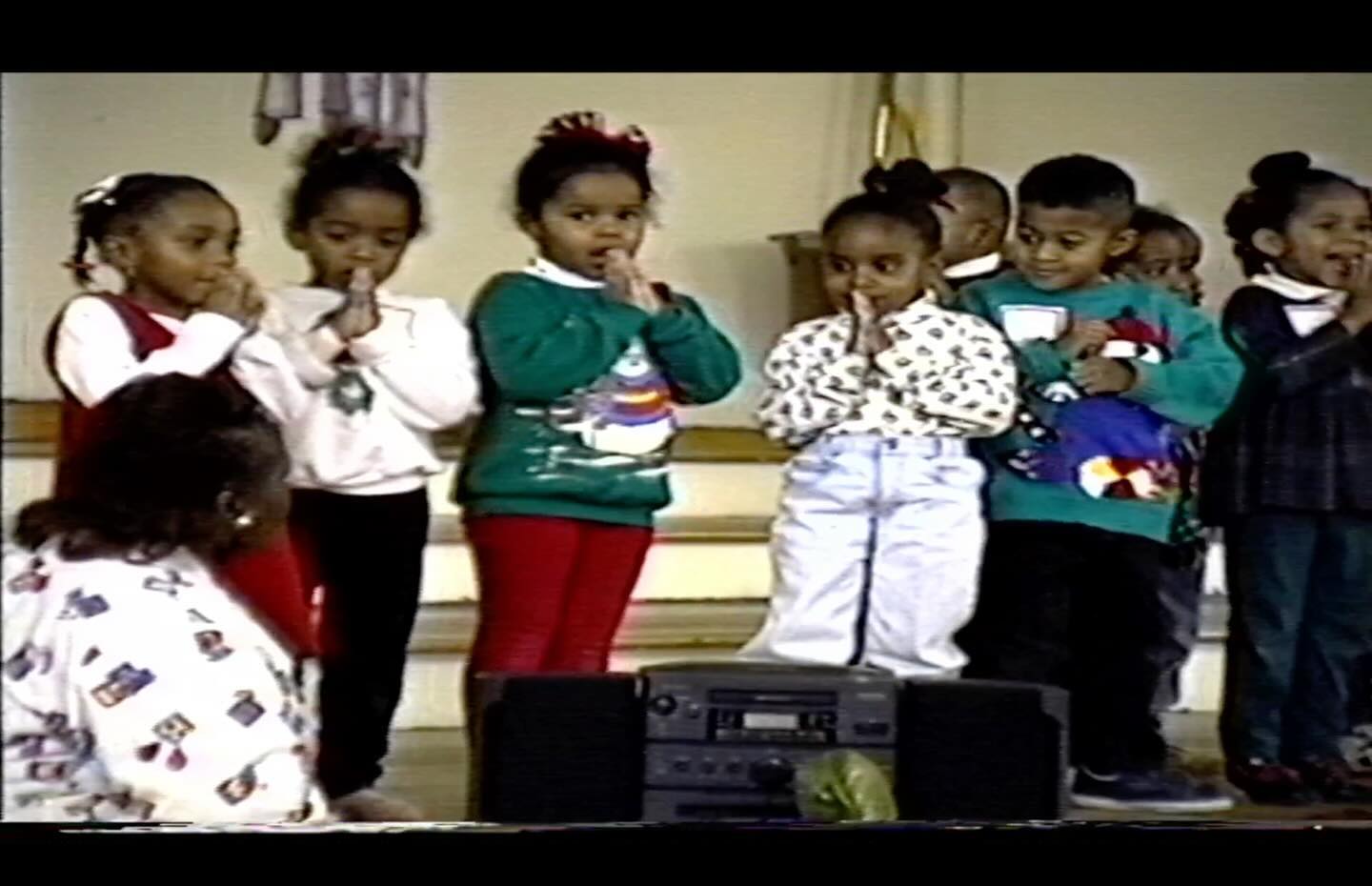

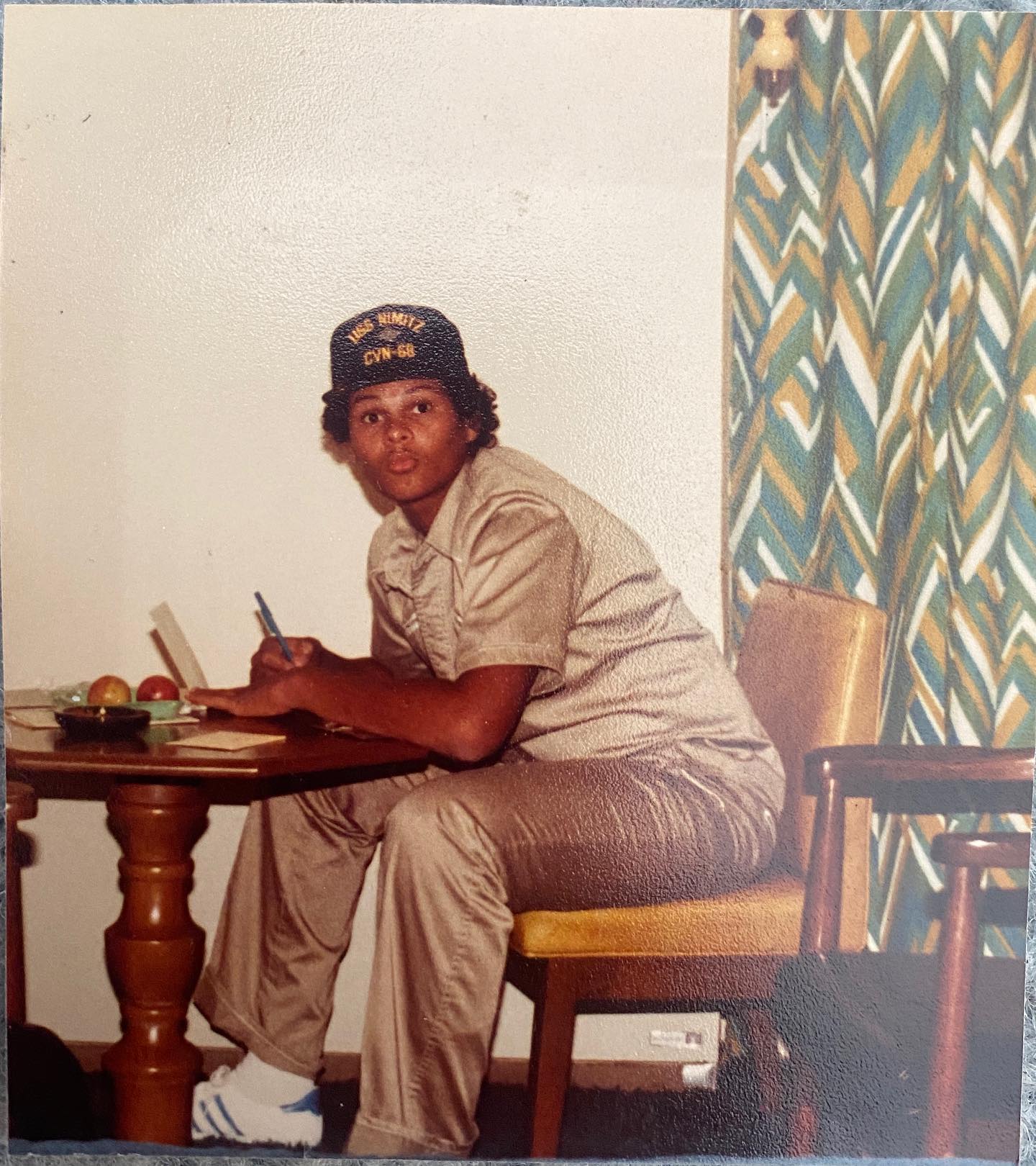

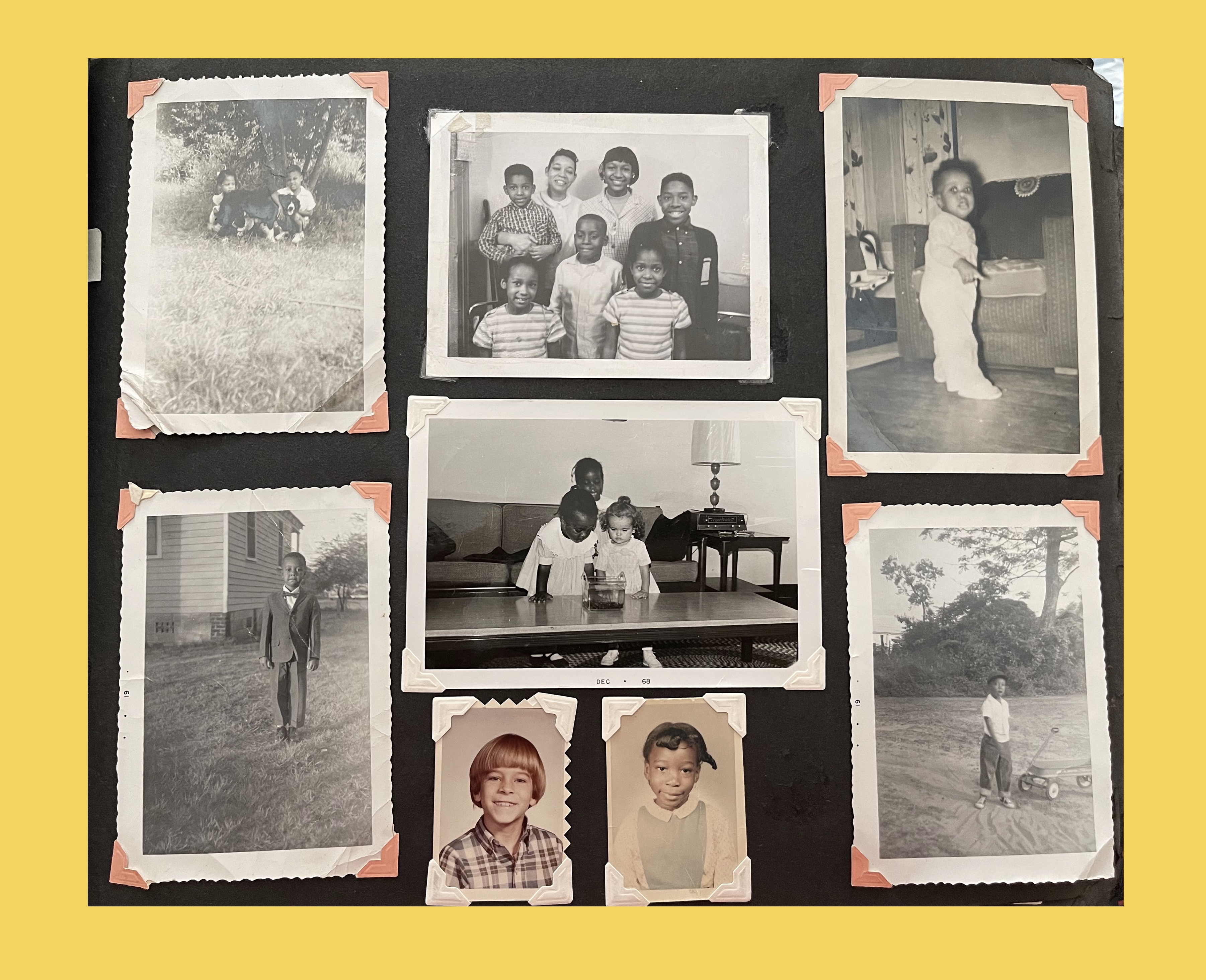

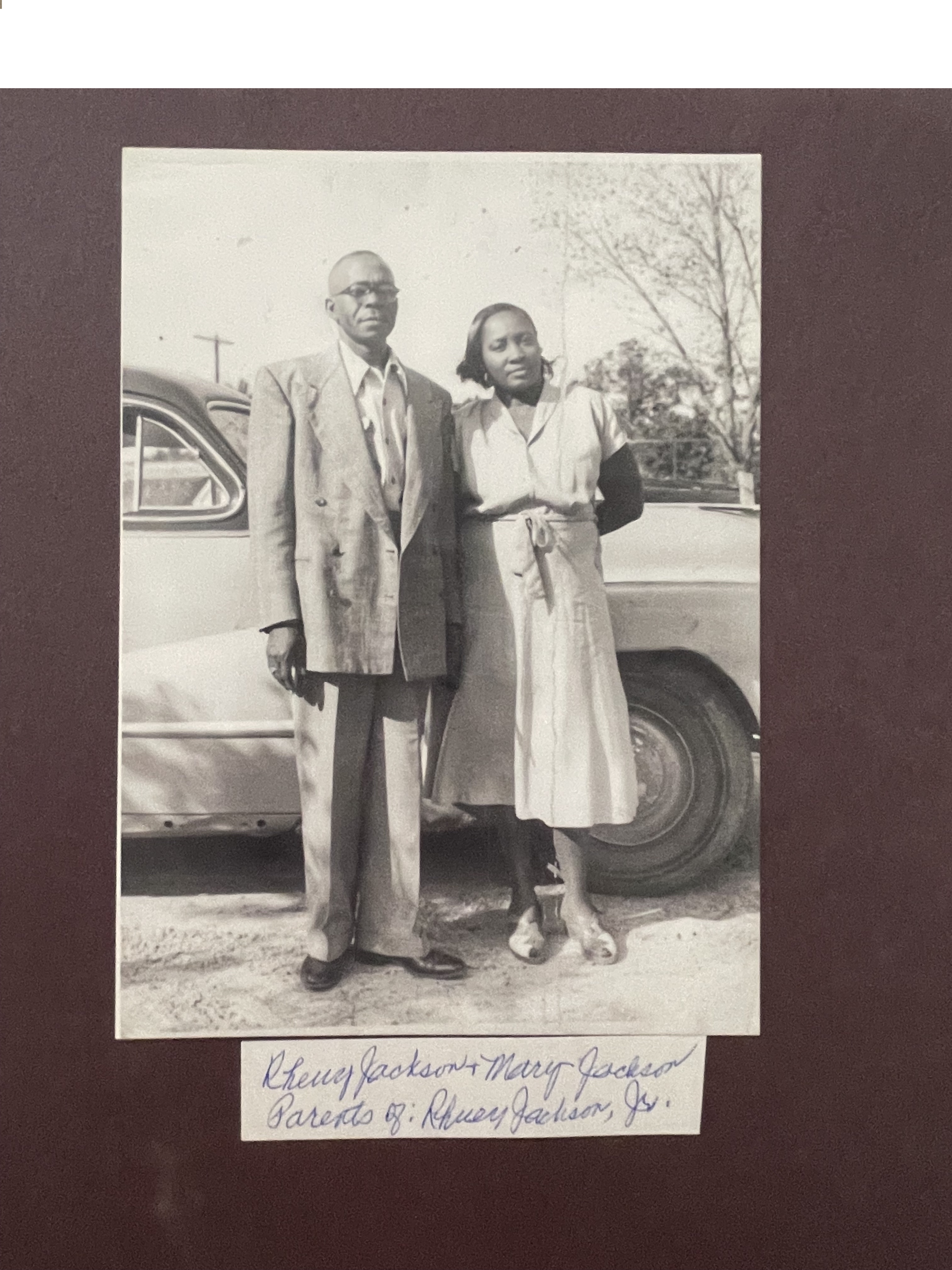

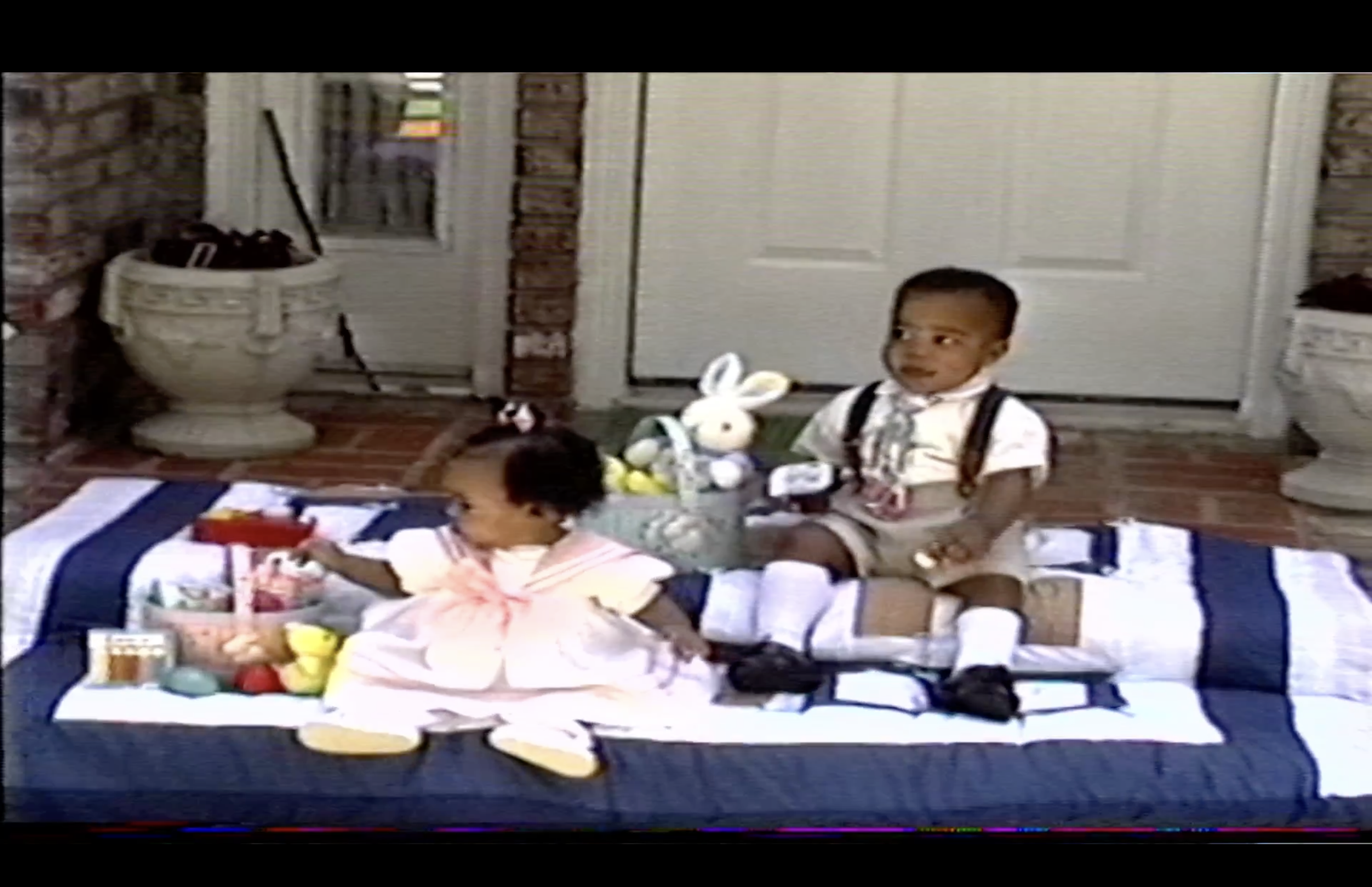

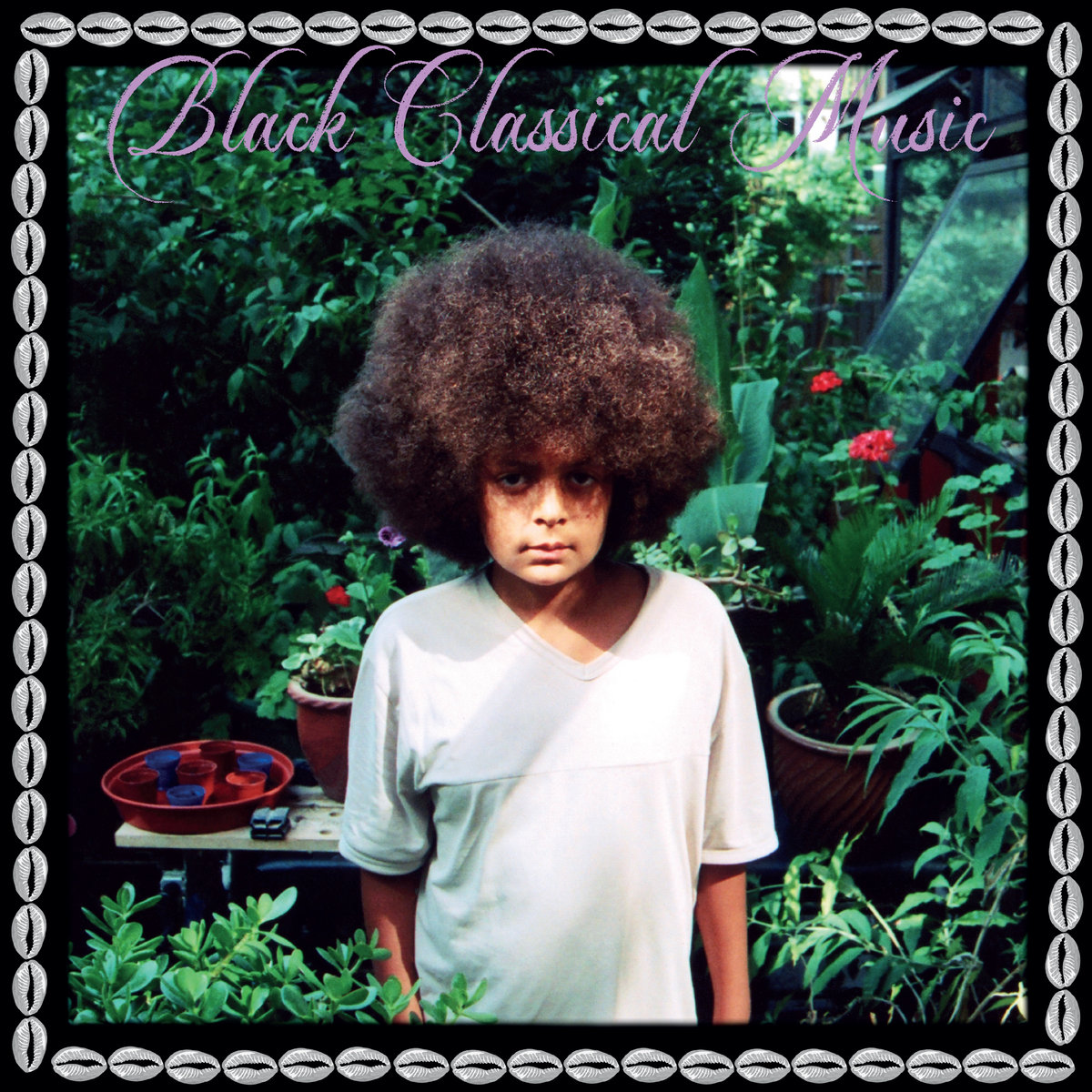

CAROLINE’S MEMORIES

Born in Birmingham, Alabama (U.S.A.) in 1996, Caroline Japal is a visual artist, photographer, and creative director. With an intense interest of her own Black southern American roots, she creates work that explores the connections between identity and place by combining moving and still image, print, and object making. In her practice she uses archival research, first-hand accounts, and personal artifacts to create work that aims to explore the interconnectedness of Black artists today and the ties to their own personal histories.

Through confronting the realities of loss and grief, AKIN was created as a vessel to carry the history that had died with many ancestors before her. She describes this project as a “reconnection journey” that brings her back to her roots through learning and listening to the stories of those that come before her.

“As a Black American, our history was systematically erased. Our ancestors were ripped from our families and homes, our land, our culture, and languages. Since 1619, when the first ship carrying enslaved peoples of Africa landed on the shores of Virginia, and for the next 350 years my ancestors would be forced to find ways to pass down their own history, culture, and belief systems as best they could and be responsible for preserving what little they were able to hold onto about their homeland. AKIN is not just a journal documenting my personal journey of the discovery of who I am and where my people come from, but it is a love letter to the many Black people who came before me and fought like hell to persevere, so I can be here today to live my life as freely as the systems I’m subjected to live within will let me.”

Desktop: Hover on images to listen / Mobile & Tablet: Click on images to listen . Images courtesey of Caroline Japal.